Turning the tap on a safer workplace

“I’ve always taken a great deal of pride in my work,” says Sylvan Daugert, superintendent of public works for the remote Village of Masset in Haida Gwaii.

By Susan Kerschbaumer

Clearly this feeling is warranted, given that Daugert is tasked with the heavy responsibility of supplying safe drinking water to the 850 village residents and the 450 people of the adjacent First Nation's reserve. Daugert, who has worked in the public works for almost 20 years, sees up to 1.2 million litres of water per day pass through the water treatment plant in the small fishing village on Graham Island.

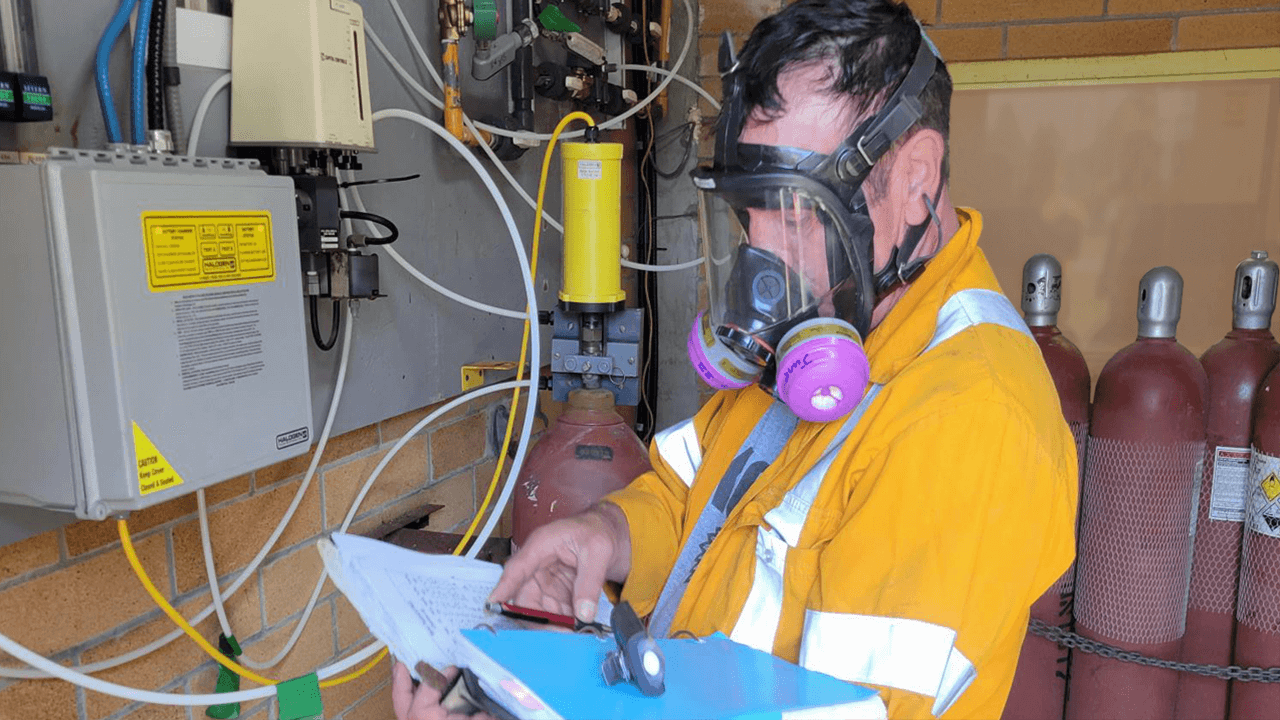

It's not just the safety of residents, however, that weighs on him. Water treatment, like a number of other industries, requires the use of a toxic process gas (TPG) — in this case, chlorine. Chlorine gas is used to disinfect the water at the plant, and to provide residual disinfecting so that the water stays potable from the time it's treated until it flows out of the taps of Masset homes — usually about two days later.

Chlorine gas, though, is corrosive to skin, eyes, and the respiratory tract. Long-term exposure can lead to lung disease. And at high levels, it can be life threatening. So, while the chlorine helps keep residents safe, gaseous emissions during the treatment process can pose a danger to workers.

Inspection triggers a change in course

"WorkSafeBC officers went through everything and identified some problem areas," says Daugert, reflecting on that nerve-wracking day in June 2021. After being rescheduled due to a weather-induced plane cancellation (a not-uncommon occurrence in this isolated area), the inspection happened on a day that Daugert was suffering some untimely side-effects from a COVID-19 immunization. "I was concerned they'd take my physical discomfort as a sign of guilt," he says.

Daugert wasn't judged for his nerves, of course, but the outdated plant — built in the 1970s — was found to be significantly lacking in many areas. The problems were extensive, and 11 orders were issued in July 2021.

Adjusting the flow to meet a goal

Daugert's small team was faced with a rigorous to-do list: installing new gas monitoring equipment, reconfiguring the ventilation system, upgrading the emergency shower system, developing new chlorine exposure control and emergency response plans, providing staff safety training, and more.

WorkSafeBC occupational hygiene officer David Ogilvie helped Daugert work through the lengthy list of tasks necessary to reduce the risk at the plant. "It took almost two years to work through it all," says Daugert. "I would have liked to say it took me six or eight months. I can partly blame COVID, but it's also the new reality of getting timelines from contractors, getting engineering done — everything takes longer now."

With his tiny staff and remote location, Daugert's difficulties were amplified. Each task, he discovered, had multiple facets that presented numerous obstacles. In some cases, he was forced to put in stop-gap measures while awaiting the equipment and professional expertise he required — all of which were located off-island. He needed to upgrade the plumbing for a tempered emergency shower, for example, but had to make do temporarily with a non-plumbed seven-gallon eyewash reservoir. Reconfiguring the exhaust system posed similar problems: first finding contractors willing to travel to Masset — an engineer out of Vancouver, a mechanical contractor from the Lower Mainland, and an electrical company — then shipping in the components.

On top of it all, the exposure limit for chlorine dropped to 0.1 ppm (from 0.5 ppm) while they were trying to upgrade the gas monitor. That meant their monitoring equipment required further adjustment to protect workers at even lower levels of chlorine than prior to January 2022.

Patience, perseverance, and a willingness to change holds water

"Toward the end of 2022, we could all start to see the light at the end of the tunnel," says Daugert. "The procedures were just an edit away from being a workable document, the plumbing had been 90 percent squared away, and we had a new alarm." Finally, in mid-March 2023, with the orders fully resolved, the efforts to reduce the risk of chlorine exposure in their workplace were producing positive results.

According to Ogilvie, Daugert and his team were positive and persistent, and the improvements they made were impressive — including emergency response and exposure control plans that, after several drafts, are now "accurate, robust, and complete."

Daugert praises Ogilvie for his open communication, and he says that he had to "lean into the process," despite initial struggles after so many years of the status quo.

"I learned so much," says Daugert. "I can see in retrospect that we really did need to up our safety procedures. It was tough to do, but it was needed to ensure our workers are safe from the dangers of chlorine exposure."

For more information

Download WorkSafeBC's self-assessment tool to help you understand the risks of toxic process gases and identify control measures. You can also learn more about WorkSafeBC inspections on worksafebc.com.

This information originally appeared in the Fall 2023 issue of WorkSafe Magazine. To read more or to subscribe, visit WorkSafe Magazine.